TL;DR

Germany’s economy has seen no real GDP growth since 2019.

Rocked by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war, Germany is facing three key structural supply-side limitations:

- A switch from Russian natural gas to liquid natural gas from overseas increases energy prices.

- An accelerating demographic transition will see the working population plummet by 7 million workers by 2035.

- Bureaucratic government structures and long approval processes slow down an economy that needs more flexibility.

Across the political spectrum, these limitations hinder policymakers’ priorities.

- As a consequence, Germany’s center-left coalition increasingly advocates for supply-side reforms.

- This mirrors the rise of American “supply-side liberalism”, i.e., a center-left movement that advocates for the targeted reduction of government regulation with the goal of boosting growth rates and incomes.

This results in the following government actions:

- Several legislative acts, cutting approval times for new railroads and renewable power plants.

- An easing of environmental review requirements for infrastructure projects.

- An immigration reform mirroring the Canadian model, with more controlled refugee migration and a meritocratic, fine-tuneable points-based skilled immigration scheme.

It is to be decided if these and future policies will be ambitious enough, as several of Germany’s ideological features could stand in the way:

- Immigration-skeptical views could hold down skilled immigration levels

- Environmentalist policies could slow down sectors that are economically important but not essential for the clean energy transition.

- Persisting demands for rent controls or electricity subsidies could slow the efficient build-out of housing or energy infrastructure.

If these impulses are kept in check, though, Germany might embrace the kind of economic reform that could boost long-term growth, accelerate innovation, and increase wages across income levels.

Introduction

Germany’s national mood has turned negative. All political parties agree that the economy is in trouble: real earnings are falling, rates of construction are down, and heavy industry is offshoring energy-intensive production. In the aggregate, the country has seen no economic growth since 2019. For comparison, American readers of this post have become markedly wealthier over the same period, with real GDP rising from $19.2 to $20.3 trillion. Germany flatlined at $4 trillion.

To change this, policymakers need to tackle three key challenges: high energy prices, a shortage of skilled labor, and bureaucratic hurdles. All of these are supply-side limitations, i.e., the economy is not as productive as it could be due to costly energy, scarce labor, and a slow-moving regulatory state. Unlike the 2008 recession, stoking consumer demand is not advisable and would be actively harmful, with inflation standing at 6.1%.

Following German economic discourse over the past few months, we observed that more and more government actors do realize the need for supply-side reform. In a recently published ten-point dossier, the governing coalition (made up of the center-left SPD, the environmentalist Greens, and the economically liberal FDP) lays out their policies to improve Germany’s productivity: reducing lengthy approval procedures, increasing skilled immigration, reducing bureaucracy, and accelerating the build-out of the country’s renewable energy supplies. Olaf Scholz summarizes the attitude behind this policy push like so:

“Only together will we shake off the mildew of bureaucracy, risk aversion, and despondency that has settled over our country for years and decades. This blight paralyzes our economy and causes frustration among the people in the country who just want Germany to function properly.”

We are excited about this new tone, especially as it resembles Derek Thompson’s “abundance agenda.” Known to people who are steeped in US economic discourse, this set of center-left ideas aims to increase material abundance, against which extensive environmental reviews or lengthy approval processes for infrastructure need to take a backseat. The goal of this is to enable all social classes to get more access to the goods and services they want and need. Less abstractly, families should be able to enjoy good public and private transport, affordable housing, and inexpensive energy.

Aiming to boost a stagnant economy, Germany’s center-left government now also begins to scrutinize a set of regulatory policies that they themselves traditionally support. While doing so, they face opposition from politicians in their own parties who continue to advocate for policies like electricity price caps and rent controls. These hold-outs, in particular, need to be persuaded that the status quo or short-term price controls demand-side measures cannot solve Germany’s shortages in energy, labor, and housing. Rather, the country’s structural challenges require extensive supply-side reform.

Energy: There’s not enough of it

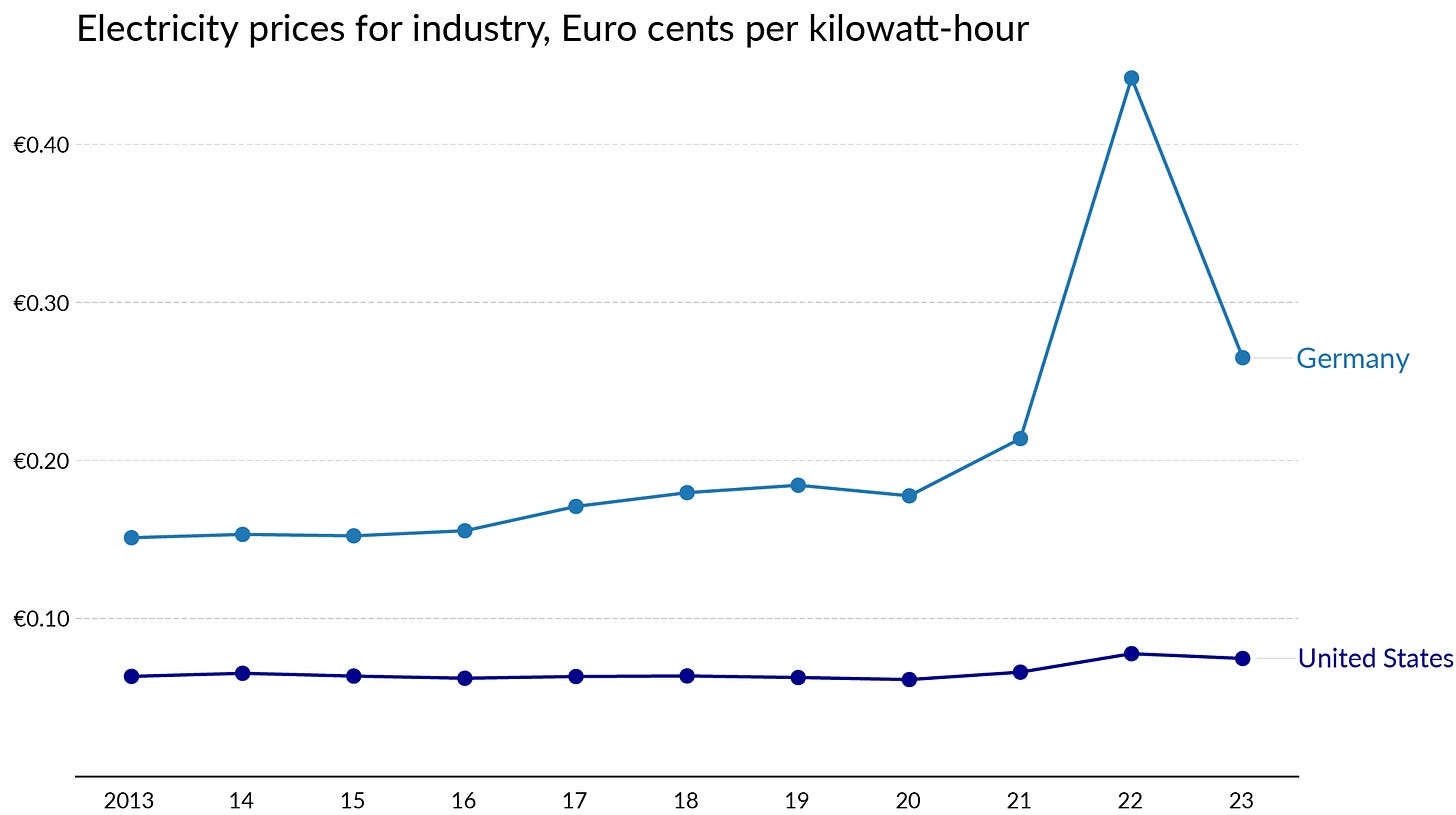

Cheap energy makes an economy competitive, as the price of gas, oil, and electricity directly impacts the price of most goods. Germany never reached the low energy costs that the US enjoys. But by opting for Russian natural gas instead of liquified natural gas (LNG) from overseas, Germany pushed prices low enough to power a productive export-oriented industrial sector. Germany’s bet on amicable trade relations with Russia has now turned bad, as Putin’s war and the subsequent end of gas exports led to a record spike in natural gas prices in 2022.

The government’s immediate response has been encouraging. As gas prices spiked, it showed a rare capacity to build fast: Bypassing burdensome approval processes, LNG terminals were constructed within 200 days. In plans to build further terminals on the island of Rügen, the federal government is tackling local NIMBY opposition head-on. The German government termed this new-found ability to build fast “Deutschlandgeschwindigkeit” (German speed), a meme we approve of.

Still, as seen in the chart above, gas prices are higher than before and are expected to stay at higher levels for years. And even though gas power plants make up only 14% of Germany’s electricity mix, they are needed to close the gaps of intermittent renewable energy production. As a result, the increased marginal cost of operating gas power plants pushes up the average cost of electricity, which will push electricity prices to above pre-2019 levels for years to come.

It’s not a novel idea that high energy prices could be lowered by increasing electricity production, and to its credit, the current government is attempting to do so with renewables. The Greens, in particular, are accepting that building more energy infrastructure may require moderating longstanding environmentalist ideals. As the build-out of renewables is hampered by slow-moving approval processes and NIMBYism, the Green-led economics ministry has given the construction of renewables “overriding public interest,” bypassing local opposition and concerns about biodiversity. On top of that, environmental impact review requirements are dropped for most renewable energy projects. This prioritization is producing results: renewables now regularly account for 30-50% of overall energy production.

However, the government acts less like an economist when thinking about nuclear power. As the Greens stuck to long-held anti-nuclear attitudes, the final three nuclear power plants were shut down this spring.1

1 Reactivating nuclear power plants is fairly unlikely, given that energy companies have been planning shutdowns for a decade, with demolitions now slowly underway. Consequently, even a shift in political power, such as the Greens losing influence in two years, won’t make it possible to turn them back on. There is still stuff to argue for here, though. For instance, Germany obstructs amendments to EU rules, which currently hinder France from investing more in its nuclear power plant fleet.

The resulting price hike would normally get the energy-intensive industry to push for compensatory electricity production. Instead, some politicians in the SPD and the Greens are considering to subsidize their electricity demand. Supported by a still-strong corporatist amalgam of large industrial company associations and industrial labor unions, such subsidies might help a couple of companies, but they stand in the way of structural economic reform: Energy subsidies will lower firms’ incentive to develop energy-efficient processes while stifling the potential of cleaner and more innovative companies to outcompete them.

Instead, the large funds required for such subsidies (~€4b/y) could support promising programs to create markets and power plants for hydrogen or top up existing R&D funds for fusion and deep geothermal energy.

Labor: A workforce in decline

An economy not only needs cheap energy; it also needs a strong and educated workforce. Long-term labor supply can be increased by boosting birth rates or immigration. Germany doesn’t look so good on either count: The bulk of Germany’s baby boomers are about to retire, and skilled immigration is low. With continued below-replacement birth rates and no policy intervention, the German Institute for Employment Research predicts a drop in the working population of 7.2 million people by 2035, from 47.3 million workers to around 40.2 million. More than 40% of German companies already report that shortages of skilled labor are hindering greater production.

Germany thus needs more skilled immigration. Upping immigration rates presents an all-around win: migrants enjoy far higher wages and better living conditions than at home, and Germany and the world will see higher growth rates as migrants can be more productive in Germany. The country has the potential to ramp up immigration: within Europe, it is migrants’ favored destination, though this is less true for high-skilled migrants, where Germany ranks somewhere in the middle compared to other OECD countries. Changing German culture to be more welcoming to foreigners is hard. But immigration reform is a straightforward next step.

Here, the government comes closest to a clear pro-growth vision. Doing something that the US political class has been unable to achieve, the coalition chose the Canadian approach to immigration: Increasing control of irregular migration while introducing a new points-based, skilled immigration system. This might allow the government to escape debates between two narrow positions: open borders vs. closed borders. Instead, if the government wants to follow the green line in the chart below, it can use this new technocratic system to slowly ramp up immigration to the required levels of 400k a year.

Vowing to build on this reform, the government plans to further reduce the bureaucratic load faced by immigrants. Similar efforts to reduce bureaucratic burden are starting across other parts of government, as close to everyone recognizes that the government apparatus needs to become more nimble.

Bureaucracy: Price controls and fax machines

The consequences of Germany’s bureaucracy and intermittent use of price controls are most obvious when looking at the country’s persistent housing shortage. In Berlin alone, rents have tripled over the past 18 years. When you buy into the Housing Theory of Everything, you will already know the many harms that a lack of housing causes, including decreasing disposable income, limiting economic mobility, reducing the production of new ideas, and disincentivizing family formation.

Vowing to build more, the coalition isn’t on track to achieve its goals, building only 295,300 out of 400,000 planned housing units in 2022. Rising interest rates partly explain this. But the government adds to the construction sector’s slow-down by limiting construction subsidies to projects that follow ever-more strict energy efficiency standards. On top of that, the discourse still hasn’t moved on from discussions of rent control, as the SPD’s parliamentary faction recently demanded national price caps. This would only limit future housing supply, a bad outcome if we want more immigrants in areas with strong economic activity.

Though faster than two years ago, the build-out of infrastructure is still fairly slow, as wind farms take an average of four to five years to get licensed, and the construction of a vital long-range transmission line between South and North Germany was delayed by years. The slow, paper-based style of governing that leads to such slow-downs isn’t anyone’s goal. But with companies enjoying stable business and little demand for transformation, government agencies faced little pressure to modernize, leaving incoming policymakers with technologically outdated governing structures.

All of this leads to a similar political situation to the one that gave rise to American supply-side liberalism. As bureaucratic structures are stunting everyone’s priorities, whether climate change mitigation or more private investment, political factions beyond the economically liberal favor both modernizing the government apparatus and getting rid of burdensome regulation. If we only look at the names of major German legislative acts, we see that this frustration has its effect: Half of them are called “[Something] Acceleration Act,” from the Approval Acceleration Act over the LNG Acceleration Act to the Procurement Acceleration Act.

Doubling down on sustainable, long-term growth

Further reform is already supported by large parts of the coalition, the major conservative opposition party CDU, and leading economists. A key determinant of future reforms’ success will hinge on the coalition embracing this support. Chancellor Scholz has recently done so with a proposed “Pact for Germany,” offering to work with state-level government and the opposition to boost growth, accelerate planning, and attract more skilled workers. But, as some in the coalition are doing now, they could get side-tracked by contentious debates on electricity subsidies for heavy industry or price controls on housing.

If the government instead doubles down on supply-side reform, the long-term benefits could be large. Yes, Germany is already a rich country. But by becoming more prosperous still, individuals can stay healthier, have better jobs, travel further, and have more leisure time. Government can do more, too, as it will have more funding to strengthen the welfare state and invest in research & development. Finally, by getting more room to breathe, businesses can use their industrial finesse to build the kind of clean industrial technologies the world needs.

Many within the current coalition understand this. To support them, pointing to the past and current shortcomings of German economic policymaking can provide valuable insights. But it’s also worth acknowledging that Germany has, in important areas, stopped messing around and is picking policies that follow the tenets of supply-side liberalism. By moving forward with these and further reforms, Germany can get out of its economic malaise and lead Europe toward a cleaner and wealthier future.